Assessing and treating Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

What is Complex Trauma?

Trauma often describes a single event which we associate with accidents, traumatic medical procedures, accidents and violence. In recent years there has been increasing recognition of the psychological impact of prolonged, recurrent and often interpersonal trauma, such as psychological, sexual or physical abuse in childhood, or chronic partner violence in adulthood. This type of trauma has been termed Complex PTSD (C-PTSD) or, when in childhood, developmental trauma.

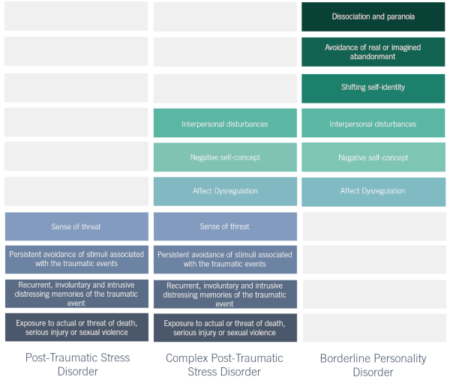

Isolated traumatic events generally lead to isolated psychological responses. These can include increased anxiety and emotional arousal, re-experiencing the event and avoidance or numbness. This is a typical diagnosis of PTSD. The complexity of C-PTSD is that it is multifaceted, with symptoms compounding those of PTSD. The particular characteristics of C-PTSD are not unique, but viewing each presenting symptom separately is likely to undermine the condition.

“Approaching each of these problems piecemeal, rather than as expressions of a vast system of internal disorganization runs the risk of losing sight of the forest in favour of one tree.” (Van Der Kolk, 2009)

The impacts of developmental trauma are not limited to social and psychological factors. The Adverse Child Experiences (ACE) study (Felitti, 1998) provided evidence that traumatic experiences in childhood have significant long-term health implications. Even half-century later, these experiences were highly correlated to heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, and other life-threatening physical conditions. For this reason, C-PTSD should be seen as a significant threat to public health.

Developmental trauma vs. PTSD

The evidence suggests that most complex trauma originated in childhood, with about 80% of those responsible for child maltreatment being children’s own parents. The prolonged trauma experienced may have fundamentally altered the individual’s personality, and children who are abused repeatedly often experience developmental delays. Therefore, C-PTSD is a combination of both biological and experiential factors, combining elements of PTSD and personality disorders.

PTSD, as a diagnosis, does not incorporate complex issues arising due to the effects of the trauma on development. Moreover, many forms of interpersonal trauma do not meet the definition for a traumatic incident as they do not involve “actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others” (DSM-V, p.271).

C-PTSD has only recently been added into the ICD-11 (2018) but was omitted as a discrete diagnosis in the DSM-5 due to its similarity in presentation to both PTSD and Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD).

C-PTSD and Personal Injury Cases

Contrary to common logic that may suggest that those who have endured traumatic experiences as a child are more resilient in later life, the unwelcome truth is that this is not the case. There is no ‘silver lining’ for child trauma victims without the implementation of appropriate, evidence-based therapeutic interventions. Instead, trauma is more akin to a filling bucket, which, with just one more stressful event poured in, could easily overflow. For this reason, it is critical that complex developmental trauma is not only recognised by the wider society, but that those concerned with personal injury claims for this population understand the cause and effect of the condition and the various contributing factors.

A recent case undertaken by an expert witness psychologist illustrates this point. The case concerned a young adult whose C-PTSD symptoms spiked dramatically following a road traffic accident in adulthood. The traumatic associations that were formed in childhood were exacerbated by the events surrounding this incident, rendering the accident far more distressing that it could have been for a healthy individual. The trauma experienced did not meet the criteria for PTSD, but nonetheless brought underlying trauma to the surface.

C-PTSD and the Family Courts

Central to traumatic stress is the inability to control internal states – emotions, thoughts and beliefs become disorganised. As a child, the reliance on guidance to respond is in line with the behaviour of their caregiver; the more disorganised the caregiver, the more disorganised the child. When the caregiver is the source of the distress, children become unable to modulate and adapt to states of arousal. Furthermore, this leads to insecure attachment patterns causing difficulties in relying on others for help. Individuals with C-PTSD live constantly on a knife-edge between fight or flight. In family cases, an awareness of C-PTSD symptoms is valuable for assessing the extent of harm and assessing further risk in previously traumatised children.

C-PTSD and the Criminal Justice System

Youths suffering with C-PTSD will often display a variety of impulsive and self-destructive behaviours. Traumatised children are often misunderstood, as their efforts to regulate emotional distress can lead to challenging behaviour. In the absence of understanding caregivers, youths with C-PTSD can often be labelled as ‘defiant’, ‘unmotivated’, and ‘antisocial’. Unpredictable responses from caregivers leads to a lack of predictability in later life. This interferes with the perception of others, their surroundings and effects of their actions. Therefore, there is little planning or thought behind their behaviour, and they may fail to evaluate consequences. This demonstrates the connection between reckless and potentially criminal behaviour and the underlying mechanisms of C-PTSD. For those who are seemingly stuck in perpetual negative cycle, it is useful to understand that new situations are viewed as a threat. This may explain why they favour familiarity despite known risks.

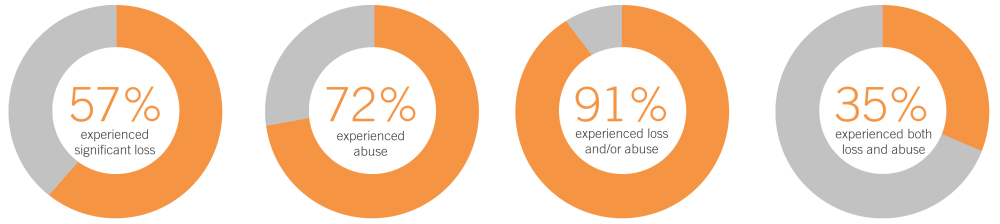

Source: Wright, S., Liddle, M., & Goodfellow, P. (2016). Young offenders and trauma: experience and impact: a practitioner’s guide. (Based on data from Boswell (1996))

Experiences of trauma in developmental life stages inhibit fundamental neurological development. The ability to adaptively integrate sensory, emotional and cognitive information and make sense of the world is hindered. This sets a foundation of dysfunctional stress responses, leading to substantial increases in the use of health services and maladaptive coping strategies (i.e. substance abuse). Research has showed that the majority of young offenders in the UK have experienced abuse and neglect.

Looking for a trauma specialist? Find an expert